Brampton Manor is back in the news again for another round of stunning A-Level results (shocker). As an alumni, my heart secretly swells with pride seeing so many talented young black kids go on to do amazing things and surpass even what I thought was possible. The discourse surrounding Brampton Manor on Results Day is always interesting, with a little bit of fact, lots of fiction and a constant echoing of ‘Black Excellence.’

The concept of ‘Black Excellence’ dates back to the Civil Rights era in the U.S, created to applaud and empower black people who triumphed in the face of adversity and racial disparities. In recent years, the term has come under fire, with people directing valid critiques at it. Whilst I understand and agree with the critiques, I don’t think the concept should be condemned and discarded completely, it is still meaningful to me. In this post, I speak about Black Excellence very specifically, that is, in terms of high performing young black students doing well academically. I’ve conceptualised Black Excellence as having a dual character, on one side, the label is used to compliment and congratulate such young black people. But the darker side, which often attracts critique, is the pressure element. The side in which young black people feel obliged to be flawless, to always excel.

I always send my drafts to my friend Holly and they incite great conversation between us. In this particular instance, we found ourselves on opposing sides. She argued that Black Excellence as an idea should be discarded but it is so woven into the black community that it feels impossible. I agree with the latter half of the statement. I think the expectation and the constant reminder to be successful, for young black kids, is often another product of being a child with parents who migrated to the U.K. Whether it is intentional or not, most of us who grew up with working-class black migrant parents, can attest to the expectation of needing to do better than them. To repay them for the sacrifices and investments they made for our sake. For me, it rang throughout my childhood like a refrain. I regard myself as very fortunate because I have very patient and understanding parents. Nevertheless, my parents still inculcated the lesson of surpassing where they started, taking advantage of the resources and opportunities I have at my disposal that they did not. Subsequently, I think whilst Black Excellence is culpable in the pressure placed on young black kids, it is not at the root nor is it one of the most significant factors in creating that feeling. This forms part of my defence, that pressure, particularly expectations about academic attainment, comes from wider phenomena. The first one I want to discuss, which I have partially touched on, is material conditions.

Our parents did not conjure these expectations from thin air. I think it is a rational response, despite how it feels. Growing up, I saw my parents always working hard, but, it did not always pay off. It was like they were running full speed constantly, but until recently, they could not catch up no matter how fast they ran. Witnessing how they did not get a ‘fair start’, pushed me to strive to fulfil the expectations placed on me. At certain points, there were times when we did not have things that I wanted and it pushed me to do more academically. Firstly, so that I could get them for myself when I was of age. I was told the way to be successful was to do well in school to get a good job, I internalised this. Furthermore, seeing how much they sacrificed drove me to force life to be fair to them. To show that their investments had made dividends and to endeavour to reward them in a way that had evaded them during my childhood.

Even if the concept of Black Excellence is disbanded, the ideology that underpins it will survive as long as the status quo persists. As long as black people remain as a marginalised group, the pressure for young black kids to do better and to be better will continue. The instruction to work twice as hard comes from a lesson learned that black people have to do an extra bit more to be given the same recognition as their white counterparts. This feeds into the expectation and the demand to be virtually flawless. Racists are already looking for any excuse to justify their bigotry, according to this logic, being exceptional means that you become faultless.

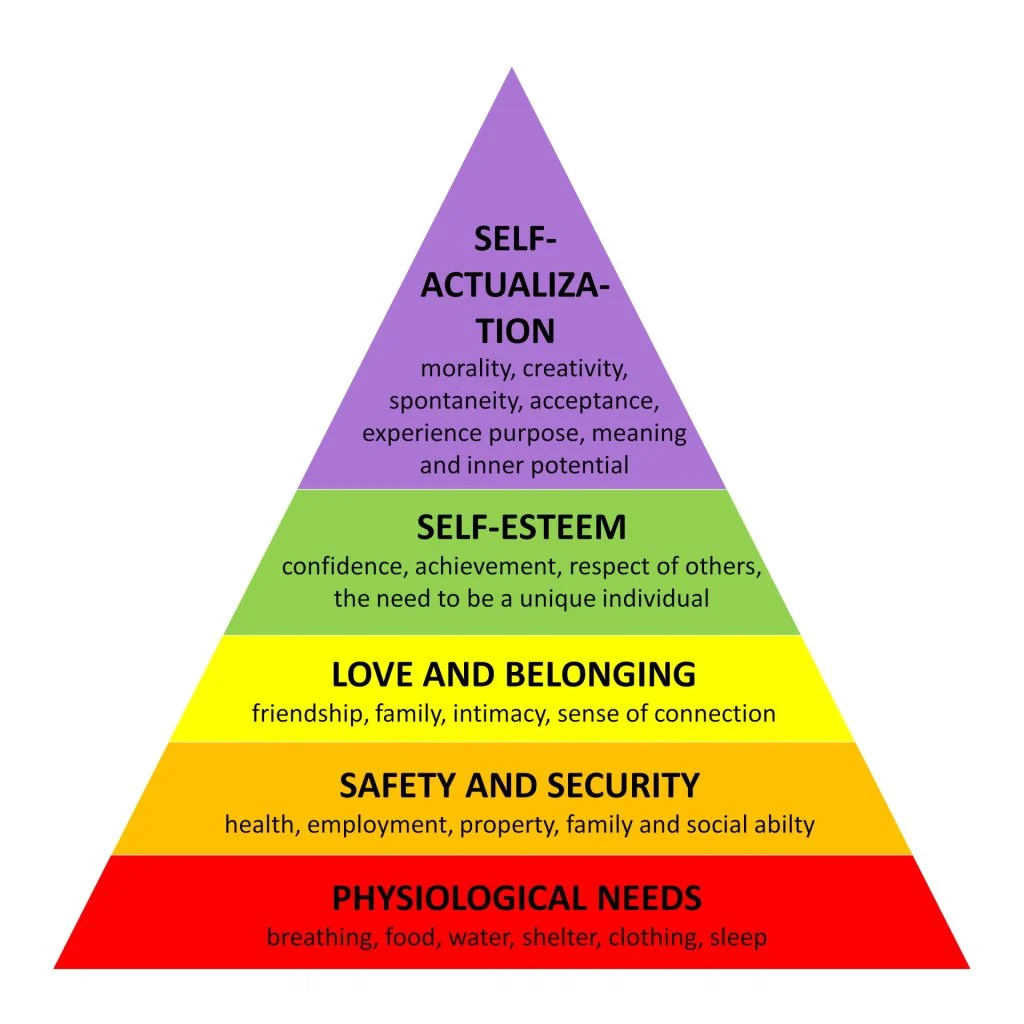

Black Excellence conceptually has developed. It has grown to expand and include multiple definitions. It is no longer just about traditional definitions of success. To me, this development is also indicative of the generational divide between migrant parents and their children. I understand it using American psychologist, Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. With this theory, Maslow argued lower-level needs must be fulfilled before higher needs are met. When applying this to myself, I see how my parents in their younger years had to fight to fulfil their lower-level needs, but me being born here and in a different generation placed me in a position where such needs were not contested and I could cast my eye further up the pyramid.

My parents migrated from Jamaica in the early 2000s. For some young 20 somethings, in a new country with a baby to take care of, there was no time, nor space to crumble or complain about pressure. They had to fulfil their lower-level needs, that is, the physiological needs and providing safety and security. But as their child, born in this new world of hope, I was given the opportunity to look past this. With the bottom needs being fulfilled by our parents we begin to long for more. To become hungry for higher-level needs, for love and belonging, for self-esteem and eventually we get to self-actualization. I think the generational gap represents the shift from the pursuit of survival to satisfaction for working-class black migrant families. Even me writing this post is an example of the privilege that I have. I can sit here to discuss and critique a concept which my parents did not. They had no choice but to accept this mantle because it was a matter of survival. They had to be successful, they had to become great in order to set the sturdy bedrock that they envisioned for my older sister and I.

The pressure and the expectations associated with Black Excellence are symptomatic as opposed to the root of the issue. We have explored one of the roots being material conditions coming from a working-class, black family. But one of the other roots are much wider. It is a societal point. As a society, we have exalted delayed gratification, praising and encouraging unhealthy working styles which produce suffering all in the name of receiving impressive monetary gains or accolades later on in life.

We joke about ‘LinkedIn Warriors’, that is people who are very active on the app, always posting about their achievements. But there is more to the joke. The existence of LinkedIn is evidence of my point that an individual’s identity and value is inextricably linked to their achievements. Typically, those who have an impressive resume of accolades receive the most connections and followers. The prominence of LinkedIn underlines the creation of identities, which we only engage with to recount stories of success.

We love an underdog story. I imagine success as a desktop. The idea of Black Excellence will never die, even though the name may. It is a crucial file in the digital folder of success. A tale of ‘Black Excellence’, of a black individual tasting success will always be a hit because blackness makes one a perpetual underdog. To still experience success despite this ever-lasting, intangible feature which can often be a point of contention (at the hands of racists) will always garner that extra bit of applause, jubilation and admiration.

Black Excellence has developed, just as our perspectives on success and our needs have. Conversations surrounding academic achievements and career trajectories have become more transparent, encouraging and diverse. It has become transparent in the sense that people are opening up about setbacks and failures they experienced on their respective journeys. These discussions have become more encouraging and diverse as people attempt to separate value from achievement, reminding you not to beat yourself up in the face of adversity. And recognising not everyone wants to be an investment banker or a lawyer or an engineer a doctor. There has been a push to encourage people to explore more career paths and to try multiple things across their career trajectory. I have not only seen it with my own eyes, but have also been party to it. My friend Olamide established a non-profit organisation, Opportunity Hub, which seeks to bring more opportunities outside of traditional careers to young people in London and to organise uplifting events for them. It urges its audience to unlock more of their creative side and to show them that the creative industry is also a source for viable careers.

The accusation that the concept of ‘Black Excellence’ places pressure on young black individuals is undeniable, I myself have been victim to it. However, as I continued to progress on my academic journey, I became quick to detach my value from ‘Excellence’ and achievement because it was just too much. Black Excellence still held a semblance of importance because it was a reminder of where I had come from, what I was able to achieve and what I had gained on such a tumultuous journey. To this day, I still find some joy and comfort in the concept, wearing it as a badge of pride. To people younger than me, I see it as a reminder that even though you are black and in spaces where the majority of people do not look like you, you have created something incredible in the face of unfavourable odds. And to people older than me, I see it as a type of homage, a thank you for paving the way and being a positive example in which I could see and try to emulate. To me, that is all ‘Black Excellence’ should be, a congratulation to black people who do exceptionally well and an acknowledgement of what it took to get there and where we are coming from. I can never divorce myself from the concept because of everything that it means to me. Yes, the pressure was, and sometimes continues, to feel suffocating. But to me, it’s more than just pressure and expectations. It’s a nod to being able to live a life that takes advantage of possibilities that are not typically associated with people that look like me and were certainly held back from people that looked like me only a few generations ago.

Articles which explore critiques of ‘Black Excellence’:

https://girlsunited.essence.com/fedback/news/black-excellence-encouraging/

https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/reports/a39570002/black-excellence/

I read something really interesting on here by Loz called Inside the Immigrant’s Head: Reflecting on western-wombed children. It discussed the idea of generational gaps in even more depth.