"They're not Third World countries, they're developing countries"

The role of linguistic policing in creating hidden histories and political narratives.

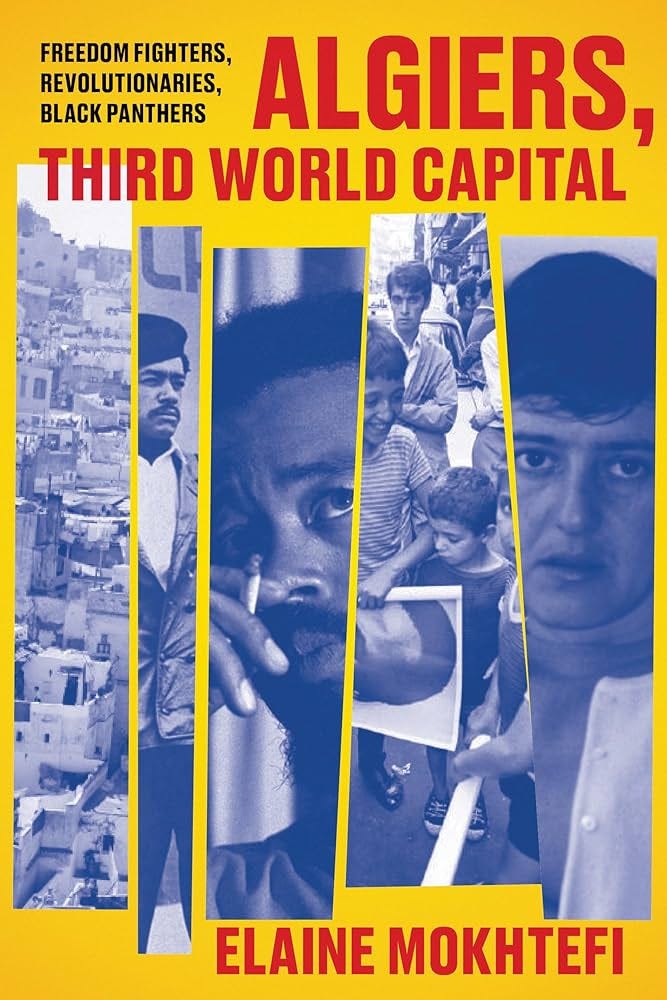

I’ve been reading this book, Algiers: Third World Capital, since this February. Reading is doing a lot of heavy lifting. I bought it around the time I was finishing up my dissertation and then got swept away by exam season, then summer and by the time all that was done it had gotten lost amongst the pile of stuff I had carried back from university that I was meant to find a place for at home. It’s a memoir about a place I don’t really know much about, safe for having a couple of friends there. It’s a memoir by Elaine Mokhtefi detailing how Algeria became one the headquarters for the Third World after it had clawed its independence from France.

Definitions

Third World countries: According to Britannica, these are countries which were not aligned with either the ‘First World’ (the Capitalist West led by the US) or the ‘Second World’ (the Communist bloc led by the Soviet Union), typically the countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Developing countries: Britannica refers to these as countries which have a ‘lower standard of living’, there are multiple metrics to measure this standard of living.

Linguistic beginnings

I can’t remember the first time I heard the term ‘Third World’, all I know is that it was shortly followed up by a renege. The person expressed embarrassment that they had used that phrase and hastily moved to replace it with ‘developing countries’.

Admittedly, it was not until I was on Twitter (I am an avid social media user), that I was made aware of the origins of the term ‘Third World’. My whole life, I have treated it as some kind of slur and refused to say it, but I saw someone say that it was the worst take ever and a linguistic failure to perceive the ‘Third World’ as an offensive term because it had been co-opted by racists discourses. This piqued my interest and here I am, trying to share the History of the ‘Third World’.

It all starts with a Frenchman. 1952. Alfred Sauvy.

In his 1952 article entitled ‘Trois Mondes, Une Planéte’, Sauvy argued there were countries who were not involved with the United States or the Soviet Union during the Cold War and their economic needs were being neglected. The tone was condescending, Sauvy used ‘Trois Mondes’ as a clever play on the phrase ‘tiers etat’ (third estate) which described the third class of people living in late 18th century France, underneath the monarchy and then the nobility. Sauvy presented the Third World as an inferior bloc.

The Third World - Origins and Construction

Robert Maisey described the Third World as an “ambitious political project premised on a moral alliance of anti-imperialist states pursuing an agenda of economic development, national sovereignty, and peaceful coexistence”. Inaugurated at the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia, 29 representatives from Asian and African governments met and committed to 3 core principles: economic development, racial solidarity and non-alignment in the Cold War.

Yes, the linguistic origins of the Third World are attributed to Sauvy, but as Jason Parker identifies, it was the actors in the Global South, the actual people of the Third World who constructed and characterised the Third World - transforming it from an offensive phrase to a movement that sought to remain strong in the face of Western neocolonialism.

The Downfall of the Third World

The current state of the Third World shows that there was a failure there somewhere along the way. Countries remain economically disadvantaged and the pledge of unity seems almost non-existent with conflicts ravaging the community.

Maisey averred the Third World was brought to its knees by the Capitalist West. Upon refusal from Third World states to accept aid from Western financial institutions, the West intervened by orchestrating assassinations of Third World leaders and replacing them with dictators who were willing to support Western interests at the expense of their national sovereignty and the economic development of their populations.

We have to look no further than the assassination of the socialist leader Patrice Lumumba in Congo in 1960 or the Chilean socialist leader Salvador Allende in 1973 to corroborate Maisey’s argument. This is one way in which the Third World fell victim to Western influence. The other significant factor was the decline of the Soviet Union. When onlookers in the Third World recognised the malignant actions of the West, some moved toward the Soviets, with a rise in explicitly Marxist-Leninist governments in Africa by the 1970s and 1980s.

But, it was too late, this was the initiation of the twilight zone for the Soviet Union, it could no longer afford to be an alternative source of financial aid for these new governments in the Third World. Subsequently, those who had followed the Communist developmental model had to abandon it in favour of Capitalist financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank to pay their long term debts.

The Importance of Language

This takes me back to the tweet!

In popular discourse, the term ‘Third World’ has been swept into oblivion to supposedly uphold political sensitivities. But in doing so, it has dismissed an entire historical chapter. This chapter presents an alternative depiction of the Third World, one which rejects the helpless and vulnerable image that has often been circulated about populations and leaders alike in the Global South.

It also reveals the underhandedness of the Capitalist West and forms connections between topics which are often only spoken about in isolation. It is very interesting that when we learn about the Communist and Capitalist dichotomy, colonialism in the late 20th century is often left out even though it holds significant weight in the conversation. Maybe it's because Capitalism and its role as a proponent of neocolonialism undermines the progressive-thinking associated with 20th century Capitalism.

However, I don’t think frankness and nuance are necessarily dichotomous. I think sometimes frankness is needed, we need to be direct and call a spade a spade. And that’s what creates complexity. Trying to find a way to reconcile and build bridges between what appears to be two wildly different philosophies because that is how the world works. Using language to sanitise histories only does a disservice to History. It dims the political and intellectual climate we currently live in by only giving us a glimpse of what our past really looked like.

Demands to decolonise the curriculum and others similar to that are met with vehement opposition, with claims that we have fallen victim to wokeness. But, for a civilisation that prides itself on rationality and enlightenment, shouldn’t we desire to get as close as we can to the full story? It will always be difficult to know the ‘truth’ about the past, but we can try to unlock the ‘full story’ by accessing different perspectives from the archives.

History can never be without bias, but that is not a limitation. We need feeling, we need meaning in our historical records and narratives. In fact, they have always been there. The example of the Third World illuminates this. The connotations surrounding the Third World were initially negative and History continues to tell it in that way, to present this as a neutral fact. But Sauvy’s depiction of the Third World was not the only one amongst his contemporaries. People that actually lived in the Third World fought back against his racist fuelled projections and instead constructed an image that upheld progression and unity. But this has been forgotten; colonial language is seen not just as the standard but as the only. Without further investigation, we would not know that the Third World prided itself on this term, we would only know that it was a derogatory term used to make us feel shame about the pernicious implications of Western colonialism.

There have been significant multidisciplinary attempts to push back against the idea that language is neutral and to interrogate the dynamics upheld by language, such as ‘reading against the grain’ and trying to find the voice of the ‘subaltern’. Language is never neutral. It is an exercise of political choice and this choice reflects power dynamics, it reflects the power to include or exclude. When we refuse to engage with the term ‘Third World’ we also refuse to engage with the History and the Politics of it. The Third World and the nuances surrounding it depict the intersection between Politics, History and language, how language and the policing of it can be used to diminish histories and perpetuate a certain political narrative.

Reading Mokhtefi’s book pointed out the importance of storytelling and language to me. When studying History, especially at elementary levels, we are often taught to only focus on the facts. That quantitative data is all that matters, i.e. the date of a revolution, the prices of necessities during a recession, the exact amount of years a monarch reigned. And whilst that is important in setting up a historical scene, the significance of storytelling is often overlooked. Mokhtefi’s storytelling revived a piece of History which has been understudied and is at the verge of being lost due to advancements in language.

Helpful Readings:

Elaine Mokhtefi, Algiers: Third World Capital, Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers (2018)

Robert Maisey, The Real Third World

Jason Steinhauer and Jason Parker, The Legacy of the Third World Project 60 Years Later | Insights

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ (1998)

Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing (2016)