The strange cases of Siccature Alcock and Eldridge Cleaver

Why interpersonal relationships are important in our politics.

Siccature Alcock

Before the days of stylish iPhones and tablets, my mum, my sister and I had a routine of crowding around the family computer and listening to reggae music on Youtube. One of my favourite artists, from a young age, was Jah Cure. The Reflections…A New Beginning (2007) felt like musical genius to me.

There was one big problem though.

Born Siccature Alcock, Jah Cure was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 1999 for two counts of rape, robbery with aggravation and illegal possession of a firearm. He and his fans denied the accusations, claiming that this was a hoax, evidence of ‘Babylon’ trying to destroy an up and coming Rastafarian star. Those that do not deny Alcock’s crimes refuse to mention it.

Violence in all forms against women is systemic. Across all boards, it feels ingrained in societies. Another response, outside of denial and ignorance, to the violence perpetrated by men in creative industries is to ‘separate the art from the artist’. Chris Brown, Tory Lanez, Octavian, and R. Kelly are pertinent examples of this.

The artists I listed are all black; there is an important disclaimer to be made before we continue any further. An oppositional argument often made is that we should save these criticisms ‘for in-house’ as we are aware black men are disproportionately targeted and punished by the Criminal Justice System. Yes, while the latter half of that statement is true, the argument in its entirety is flawed and dangerous. When we refuse to discuss these topics and instead divert to the violence committed against women by white men, we fail to hold the men in question to account.

How can we talk of community and ‘preserving’ the black race if we refuse to condemn violence against half of its population and continue to fawn at the feet of the proponents of such violence?

The Personal is Political

When discussing this concept in 1969, Carol Hanisch extended the definition of political to “having to do with power relationships, not the narrow sense of electoral politics.” Power relationships are political; determining who gets a voice, who gets representation, and who has authority within a society is political. I think it is important to investigate the interpersonal relationships of people who have been vocal in politics, especially politics regarding power relationships. When a black man commentates on and challenges the subjugation of black people whilst simultaneously subjugating black women or any women at all, it becomes difficult to believe in their calls for equality because in dynamics where they do possess power, it it is exploited.

Like many reggae artists, Jah Cure invoked political symbols in his music. Inherently, Rastafarianism is political and you can find songs where he denounces the evil of ‘Babylon’ and uplifts the ‘Lion of Judah’ and ‘Mount Zion' as signs of political liberation.

If his dream of repatriation to Mount Zion (Ethiopia), that he lyricised about was suddenly granted, would Alcock be a fit, productive member of that new society?

Putting the problematic aspects of repatriation aside, this is a genuine question. If we take the politics that Alcock espoused in his songs seriously, if we perceive him as the political figure that he crafts himself as in his music, what kind of leadership or contributions could we expect from him? Personally, I would have no belief in his capacities.

Forget capacities, how are black women meant to feel safe, as if they have also attained ‘liberation’ if one of the mouthpieces for such liberation has the track record that he does? A man that violates women should never be the face or even a spokesperson for liberty of any kind. From their actions, it is clear that liberty in their minds is not universal, their liberty is boundless and undermines the freedom and boundaries of others.

The behaviour expressed in such interpersonal relationships demonstrates that they as an individual cannot be trusted. Personally, political figures lose credibility once I discover fatal flaws in them, such as violence against women. Maybe it’s because I’m a woman and I actually take it seriously, but I refuse to venerate individuals who display such behaviour.

Intra-communal abuse is not a good sign. How can we expect you to lead us to liberation and enlightenment when you cannot even be trusted to respect those around you and manage your emotions in a manner that is safe and productive for the rest of the community?

Eldridge Cleaver

The examples I listed demonstrate that you can be a black man and still be oppressive, but I will go one step further.

The American Black Panther Party (BPP).

Often regarded as the apex of community for black people, one of its most influential members (Eldridge Cleaver) had an abominable track record concerning violence against women. This is not to undermine the work the party itself completed, it was invaluable in delivering empowerment for black people in the U.S. and galvanising other black communities across the diaspora into doing the same.

Cleaver, in his own words, described his engagement in sexual violence against women.

“I became a rapist. To refine my technique and modus operandi, I started out by practicing on black girls in the ghetto… and when I considered myself smooth enough, I crossed the tracks and sought out white prey.”

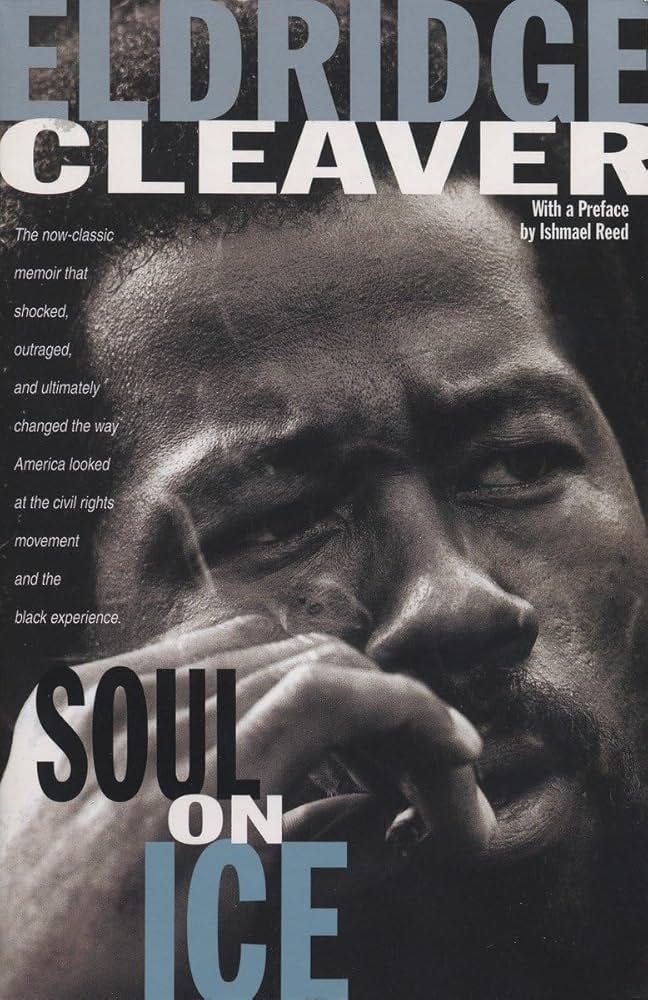

-Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (1968)

Cleaver in his memoir decried racism and the alienation of black people whilst explaining how he used his power as a man to oppress women who he perceived as powerless in relation to him. His description of violence against women in chronological order is so important. He started with ‘black girls in the ghetto’, a demographic who fall at the bottom of the totem pole of privilege and he knew this. That is why they were his test subjects. He wanted to see just how far he could push his violence against the neglected, the ignored. A sick method of judging just how much violence he could enact onto another marginalised group, the group he despised but still desired - white women.

Despite his heinous behaviour toward women in his youth, Cleaver was practically rewarded by the BPP. Upon early release from prison in 1966, Cleaver formed connections with the founders of the BPP, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. He became the Minister of Information for the Party shortly after, this was a national position. Cleaver had been convicted of rape, had admitted it in Soul on Ice, and had these confessions published in the magazine Ramparts.

Instead of a life of ostracisation he received a post in one of the highest leadership positions in a radical Party. We can re-examine BPP leaders and their inspiring essays on Black power and even lament over some of their works on protecting black women. But the credibility of the latter feels cheapened once we interrogate Cleaver and his role in the BPP, a man who was an obvious danger to women was not only allowed, but welcomed and elevated into the Party.

And yes, a few counter-arguments can be levelled at my assertion; consider the context in which Cleaver lived, women's rights were not where they are now. Many powerful men who have achieved monumental feats have a violent record with women. Cleaver committed those crimes when he was young and before he was involved in the BPP.

To respond to the first counter-argument, I think it is poor to continue to absolve men of the degradation of women in the past because it was somewhat okay back then. It should not have been permissible back then. I think we in the present have the moral duty to be honest about our past and identify when there have been moral failings, even by people who are remembered favourably by the history books and by our community. Furthermore, Cleaver did not live in the Middle Ages, he was convicted of rape and intent to murder in 1958. Rape was illegal then, it was widely accepted that it was wrong to do.

Onto the next point, my response is similar to what I have stated previously in this article. Let us hold the men in question accountable. Often, people say stuff along the lines of, “how can you criticise X and support Y when Y does the same thing as X.” I find this line of reasoning annoying and lazy. The people who criticise X are more than likely criticising Y if they know about Y. If we apply this to Eldridge Cleaver, some might say, why are you condemning a black man for a history of violence against women when you do not do the same for *insert notable white man with a similar history.* The answer to that is simple, I either do not know about the latter or I have already criticised the latter, I have more than enough time and energy to devote to condemnation.

For the third point, it is a baleful rhetoric to suggest that men are too young to know that they are perpetrating harm. In Cleaver’s case, his violence against women was not just some youthful mistake, in her memoir, Elaine Mokhtefi (who worked closely with Cleaver as he led the International Section of the BPP) reported that Cleaver was abusive to his wife - Kathleen.

Moreover, we should not reduce violence against women to a ‘youthful mistake’. Are women ever extended a similar grace, are women ever too young to be shielded from the violence and abuse of men?

The answer is no. There are multitudes of stories and experiences of girls so young being subjected to patriarchal violence. Why should men, at any age, be excused from the consequences of the harm they have caused? The answer is they shouldn’t be!

What Next?

Violence against women isn’t just a quirk, it’s a glaring character flaw that makes you not only unfit for leadership but a danger to your community. Women’s bodies are not sites of development for men, they should not be used by men to toy with, to be violated, so that men learn that abuse of any form is wrong.

Intersectionality is more than simply reeling off characteristics of our identity and ticking whether it marginalises or empowers us. We must use it as a tool to analyse and strengthen our interpersonal relationships. It is not only black men who are guilty of using the power they have to reinforce a pernicious status quo. When we look inside ourselves, we must ask, how do we use features of our identity that grant us privilege to support others, to challenge and try to dismantle harmful structures?

I am in no way preaching from a high horse. I have been guilty of engaging with material from artists who have exhibited this type of behaviour. In writing this post, I hope to keep myself accountable too. Once you have the knowledge, there is no excuse.

If we want to see real, tangible change, an amelioration in the treatment of women, we must take a stand against violence towards them. It is not enough to post an Instagram story on International Women’s Day or to make chronically online jokes about your support for women. You need to actually stand on it. An individual contribution that you can make is to stop supporting men who endanger women and to condemn people that enable that sort of behaviour.

Yes, politics is nuanced and complex, but this part should not be. You can recognise talent or political acumen, you don’t have to say that Jah Cure is suddenly a terrible artist or that Cleaver entirely was useless to the Black Panther Party. But, you do have to view these people holistically and acknowledge that they may have brought more harm than good to the community they proclaimed to save.

I think we should demand that our leaders, and the people who position themselves as political voices, operate at a certain emotional capacity and are able to treat the people around them with care and dignity. The dichotomy we have forced into politics and history between emotion and logic is senseless. To be a good leader you have to understand others, you have to consider others and that is both parts emotion and logic. Emotional analysis is not being too sensitive, it is necessary, it is a good measure of judgement.

Helpful Readings:

Carol Hanisch, ‘The Personal is Political’ in Shulasmith Firestone and Anne Koedt (eds.) Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation (1970)

Laurie and Sy Landy, ‘The Black Panther Party Splits’ in International Socialism (1971)

Ollie A. Johnson, ‘An anti-authoritarian analysis of the Black Panthers’ demise’ in Charles E. Jones (ed.) The Black Panther Party Reconsidered (1998)

Elaine Mokhtefi, Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighter, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers (2018)