"Black British culture is just chicken and chips and grime"

Deconstructing the notion of a 'Black-British' identity.

Kiara and I met properly on this app. We would engage with each other's posts which I thought was a cool, thought-provoking exercise. She has a propensity for detailed and articulate comments. It left me curious to know more about her opinions and ideas. I thought the best way to do this was to write something together, so I proposed a collaboration. And since then, we have been exchanging ideas rapidly, conversing on a multitude of subjects from university to colonial history to our shared affinity for herbal tea. We were initially going to write about engaging in Jamaican culture whilst being children of the diaspora, but with the release of the ‘Brother’s Keeper edition’ of I-D magazine, the perfect idea fell into our laps.

I think that my friendship with Adrienne has fundamentally been consolidated through podcast-length voice notes—or what some would simply call endless yapping. Her passion for history and her ability to explore and develop sophisticated arguments in such a measured way is truly remarkable. When our conversations reach a natural end, we somehow always end up discussing the granular aspects of everyday mundanities in philosophical ways. She has deepened my introspection, particularly regarding life’s deepest intimacies and the things that make me who I am. I hope our passion and commitment to the cause shines through in this piece. It is always a pleasure. Now, to the nitty-gritty.

I think when the images migrated to our screens from our favourite social media platforms, our immediate responses were not inherently critical. I speak for myself when I say I-D magazine's 'Great Britons’ piece has lingered in my mind and in my mouth, for longer than it took for me to read the article itself. The piece presents photography by Hattie Collins of Clint, Gabriel Moses and Slawn in front of the Great British flag. Thematically, the article claims to be an examination of community through the eyes of well-known black creators in the UK, further detailed through qualitative data included in the article. The project raised questions that extend beyond the concept of community, focusing specifically on the political implications of popular black creators standing before the British flag. This, in turn, sparked a broader debate on the construction and perception of the Black-British identity. Hopefully, those who insist that art holds no political significance are beginning to reconsider their perspectives.

Before we get into any analysis, I think we must acknowledge that there are multiple Black-British identities. This includes, but is not limited to, black people who are of an ethnic heritage but were born and have lived their whole lives in Britain (such as Kiara and I), black people who were born elsewhere but migrated to Britain during their childhood years and black people who were born and raised elsewhere but now currently live in Britain. Under this definition, we are all technically ‘Black-British’, but it would be a fallacy to assume that we all have the same shared experiences. We do not because there is a diversity in backgrounds which inform lived experiences.

Subsequently, Kiara and I have decided to focus on the Black-British identity that we possess. That is, the Black-British identity that is formed by the British colonial experience. We believe that ‘Black-British’ is a hybrid identity, and the ‘Black’ refers to your homeland. It is a stand in for your heritage. For us, that is Jamaica. So, our argument will be centred around the existence of the Black-British identity for black people who were born and raised here with parents from the ‘British’ Caribbean.

The Denial of a ‘Black-British’ Identity

The rejection of Britishness is not a disposition that is incomprehensible. In fact, for many who carry the weight of colonial violence and subsequent epigenetic trauma, British citizenship stands as a marker of shame. The colonial response to the 1856 Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica is a pertinent example of colonial violence and the subsequent trauma. What started as an insurrection on a plantation in Morant Bay escalated and was violently quelled with 469 Jamaicans murdered and the aggressive destruction of St Thomas parish. Understandably, British rule could only empower rage and disdain. These tragedies are not just our own. The Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya is underpinned by the experience of torture. Black Kenyans who served in the British Army returned to Kenya in 1954, inspired by the Indian nationalist movement. Motivated by this experience, they began to demand independence and liberty in their homeland. An attempt to form an intertribal government and revolt against British Rule, resulted in the significant bloodshed of innocent civilians. To know your history, is to feel your history and in this case Britain will forever rest in this imagery and sentiment of revulsion.

In the specific context of Rastafarianism, anti colonial and Pan-African principles remain integral to theological legitimacy. Within this religious demographic, to be righteous and enlightened is to be conscious of the history of Babylon, fundamentally rejecting the project of colonialism. To many Jamaicans this political disposition will not be unfamiliar. Particularly for me, my first generation British-born Jamaican father made it his duty to remind me that I am not from here. That I was a Black Jamaican and that my ancestors were from Africa. My ancenstry.com results did not undermine his stance. Moreover, his lived experience and the experience of crude racism in the 60’s and 70’s faced by my grandparents and great grandparents, further contextualised Britishness as something they could never be. British culture was foreign and difficult to navigate. It forced sociological assimilation that birthed a new set of values and approaches to living in this country as a Black Jamaican. I think my family always intended to go back to Jamaica, and most of them have returned. They are probably sitting blissfully on their verandas as we speak. As soon as my grandad returned home, he vowed to never come back to the UK. He hasn't set foot on British soil since.

The complexity of Black-British identity and the subsequent discourse has transmitted my grandfather's generation and beyond, reaching our main social media corners, Tik Tok and Twitter. An argument that gained popularity on both platforms was that there is not a Black-British identity because the demographic does not have the typical markers of a shared culture. Proponents of this view went on to provide examples of the features that the Black-British culture is supposedly missing, such as a shared cuisine and a shared language.

Firstly, I don’t think there is a lack of a shared language. The Black-British identity in question is communicated through English, that is the shared language. The question is not whether that is the sole or primary language. Of course, many Black Britons speak English and the language of their homeland. But to argue that there is no ‘shared language’, seems strange when we interact with each other in English. Yes, it is the language of the coloniser, but for many Anglophone Black Brits, that is the official language spoken ‘back home’ too. To act as if English is this foreign, non-existent language seems unfair when it is the language that has bound Britain and its Empire as well as forming bonds amongst countries within the Commonwealth. Furthermore, the existence of Multicultural London English (MLE) represents the influence of black and other ethnic identities on the English language itself.

Furthermore, I think hinging the dismissal of an ever evolving identity and culture on a lack of a shared dish is rather flimsy. To understand culture, is to understand that there are multiple interpretations and definitions of it. The best way I can explain this is by likening it to Nationalism. When I studied Nationalism in A-Level Politics, the first thing that I was taught was that there are different definitions of Nationalism - different ways in which citizens in a nation are united to engage in a shared identity. I think that this rule should be applied to how we view culture. Culture is not just archaic paintings and centuries old papers of literature bound together. The meanings of culture have evolved as time has gone on.

Even still, if we were to adhere to the ‘traditional’ markers of a culture, surely the Black-British identity fulfils some of these prerequisites. We have already established the existence of a shared language. Personally, I don’t think a singular, shared cuisine is all that important. But, the point could be made that there is a burgeoning, shared cuisine amongst Black Britons. Annually, on Christmas Day, jokes are made about the fusion of cuisines on the festive plate of Black Brits. Kwollem’s Grandma’s Kitchen featuring AJ Tracey feels like the soundtrack to my Christmas dinners, with the presence of staple Jamaican foods in a British home, being cooked by my father who was taught by my grandmother. Two individuals who grew up on an island thousands of miles away. My Christmas dinner plate typically looks like rice and peas, mac and cheese, Yorkshire puddings, roast potatoes, roast chicken and curry goat or oxtail depending on what version of red meat my dad is currently obsessed with. On the side, is either roasted vegetables or a healthy serving of coleslaw. The foods that I just listed are staples in both ‘British’ and ‘Black’ Caribbean cuisines. Despite only spending one Christmas in Jamaica with my grandma that I can remember, every year Christmas dinner feels like it’s being hosted in ‘Grandma’s Kitchen’. A site where there is a coexistence of British and Jamaican culture.

The example of food represents the dual character in the Black-British identity. It is not about being one or the other, it is about being both and both having an influence on you. As Kiara outlined, feeling like the British side of your identity is suitable for you as a black person is something that is difficult; I think it will always carry the anchor of colonial trauma. But, black people in Britain have been able to carve out an identity for themselves in the country they were born and raised in. This has been done whilst maintaining a connection and engagement with their homeland, the country their parents or their grandparents or great grandparents were born and raised in. I think to deny that, is to submit when racists and those ignorant to the complexities of British colonial history state that black people cannot be British. To do that, is to deny the intertwined nature of Britain and its colonies that have followed into the present day. To deny the influence that Anglophone, predominantly black colonies, had in the making of modern Britain - an island that is also our own too.

In defence of a ‘Black-British’ Identity

The Black-British identity is often mistaken to be a reductionist, monolithic construct. Whilst debating critically on its legitimacy and existence, we overlook the reality that multiple Black-British identities can exist at one time. I argue that this is driven by an egoistic pursuit to assert a universal truth. But ultimately what Black-Britishness means to me does not have to align with what it means to you. It would be more productive to agree that we cannot build an absolute consensus on this concept and that it is inherently subjective. Rather perhaps we can agree on an ideology of culture and how it informs our identities individually.

Stuart Hall’s writings provide critical contributions to this idea of cultural identity. He argues that cultural identity is constructed by two pillars. The first pillar positions cultural identity as a shared oneness, reflective of a common historical context. This is the true essence of the Blackness that unites the diaspora and anchors identity across dimensions. The second position emerges to present this principle of difference and fluidity. Here we are arguing that the critical and political nature of cultural identity is characterised by this experience of becoming and being. Hall describes this as acknowledging how identity is not eternally fixed but is in constant transformation and production. This involves our identities being informed by not just our ‘histories’ but the present and the future, representing a constant negotiation of power, context and culture.

Although the unanimous experience of Blackness unites us, the ruptures in our histories do not produce deterministic constructs of identity. The ways in which Black people were positioned particularly within the colonial regime, means that the past will continue to narrate to us and contribute to material contexts, but who we identify to be will exist beyond this historical framing. The continuity of cultural production means we may never completely agree on what it means to be Black-British, but I think it's imperative we agree that the culture in itself exists. Anthropologically speaking, culture exists as a complex framework of diverse experiences, customs, values, beliefs and morals that underpin our existence. So to be able to collectively attest to perhaps not being allowed to watch Harry potter in primary school or £1 chicken and chips after school, I think can affirm the existence of a Black-British culture and subsequently a cultural identity. With this concept being in constant transformation, we will never agree on what specifically compounds one's cultural identity but this captures the essence of fluidity Hall calls for in his work.

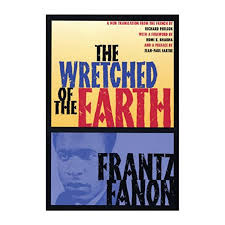

In summation, a Black-British culture and identity ought to be characterised by the transient hybridity both of Blackness and belonging to the diaspora but also this sense of Britishness- an experience of being and becoming. In The Wretched of the Earth (1963), Fanon urges us to confront colonial history while striving to cultivate a "new man," one shaped by our position within the diaspora and by the evolution of culture. This "new man" emerges through the development of a national consciousness—a true "coming-into-being" of one’s identity beyond colonial frameworks. For Black people in Britain, it is crucial to remain aware of our history within this nation, while also envisioning the future of our identity and culture. As Fanon states, the "absence of culture is the height of barbarism," underscoring the importance of critically examining our cultural identity but also the impact of neglecting culture. In doing so, we affirm the unique existence of Black-British culture, rooted in both historical awareness and forward-looking resilience.

Colonial dynamics are often, and rightfully, described as iterations of exploitation. But an adjective that is often forgotten is symbiotic. Great Britain as we know it today would not exist without its former colonies. And its former colonies would not exist as we know it today without Great Britain. I am a historian by trade. And it was inculcated into me by my university tutors to never base an argument on what-if. In this instance, what if Britain didn’t colonise the world or what if countries like Jamaica were never subjected to colonialism. Thus, I think it is appropriate to make the statement I made above. People can speculate about Britain reaching its supposed ‘greatness’ regardless of its colonial ‘prowess’ or the greatness colonies would have been able to achieve if they were not subjected to colonial overlordship and exploitation. But, the reality is, that colonialism did happen. The story of colonialism is often told as this straightforward, top down power dynamic in which the metropole simply directed and ruled over the periphery. This is largely true, but it neglects the complexity of the experience. In which instances where colonies were able to exert influence over British culture, creating a subsequent (albeit imbalanced) exchange of culture between the metropole and the periphery. This is where culture comes in.

British culture and the cultures of our homelands have many points of intersection. For many former colonies, the way they continue to operate is a legacy of British colonialism, as they were made in the image of the metropole. Subsequently, culture and politics continue to be guided by British influence. This is because across its Empire, the British colonial machine sought to bring ‘civilisation’ to its colonised populations and agreed the way to do so was to create the foundations of a modern state in these colonies that mirrored the British state. Two interesting examples of this are India and Jamaica. In both cases, insurrections against British rule were cited as evidence that the native populations were not ‘civilised’ and needed British paternalism to direct them to that point. The 1857 Indian Mutiny was followed by the introduction of the 1858 Government of India Act which transferred control and ownership of the country from company rule to the British state. Similarly, the control and ownership of Jamaica was transferred from the white plantocracy to the British state by the 1866 Jamaica Act after the Morant Bay Rebellion.

For the ‘British’ Caribbean, cultural identity is rooted in Britishness. This is not to say that it will always be, but Britishness is a cornerstone of Caribbean cultural identities and thus it is part of the story. We have to look no further than moral codes in Jamaica to illustrate this. Brian More and Michele Johnson explored this in Neither Led Nor Driven. They explained how the Jamaican social elite and British imperialists attempted to introduce a “new sociocultural religious and moral order, based on British imperial ideologies and middle-class Victorian ideas, ideals, values and precepts” to the Jamaican people. In late 19th and early 20th century Jamaica, black and coloured Jamaicans who desired full citizenship sought to emulate key features of British culture to prove they were deserving of it. The pursuit of respectability politics has been a base for mainstream Jamaican culture and it continues to this day. I spoke of this in a previous post, in which I detailed how many Jamaicans remain socially conservative due to British colonialism. British and Jamaican social and moral codes have many overlaps and this has shaped Jamaican culture.

And what about the other side? The answer is not as straightforward as understanding how Britain exerted cultural influence onto its Caribbean colonies, but Catherine Hall provides a great starting point for exploring the inverse. In 2021, Hall delivered a talk entitled, ‘Entangled histories: Britain and Jamaica in slavery and beyond’. Hall captured the essence of what we have been saying in terms of colonies influencing British culture, stating that colonies were vital for the development of modern Britain’s politics, commerce, and culture.

I used a database established by UCL to interrogate Hall’s argument. It showed an abundance of cultural sites and affiliations in Britain which were were financed with the compensation the British government gave to slave owners who had stakes throughout the Caribbean. A perfect example of this is the Bromley House Library. Located in Nottingham, one of its main founders - Reverend Robert White Almond - was able to contribute to its establishment in 1820 because he inherited money from the compensation of enslaved people in Jamaica. Almond was the recipient of the Hanbury Estate in Manchester, Jamaica in his brother-in-law’s will. He was thus entitled to the compensation the British government extended to slave owners in exchange for the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the first decade of the 19th century.*

We can see the prints of connection between Caribbean culture and British culture, both informing each other. Colonialism and the imbalanced relationship between Britain and its Caribbean colonies means that culture was influenced on both sides but in different ways. For the Caribbean cultures, their cultures were governed by Britain; the colonial power had the authority to do so in the asymmetrical relationship. The influence of Caribbean colonies on British culture is not direct in that way, but can still be found when we trace the financial history of important pieces of British culture. The reason for their existence was due to British slave owners being compensated and then investing that money into the development of British culture.

Even if we fast forward to the 20th century, we can again see the direct impact populations have had in the construction of present day Britain. For example, the National Health Service required the labour and the enthusiasm of black populations in the Commonwealth to make Clement Attlee’s vision of a welfare state a tangible reality. However, the narrative often forgets the significance of these countries in the Commonwealth in this construction.

Hall’s conception of the dynamic between Jamaica and Britain as a ‘Long History’ illustrates how their histories are intertwined. If we were to say we were just Jamaican, even then, we would still be linked to Britishness and vice versa. Traces of the other will always be found in either one of them.

Echoing the sentiment expressed by Adrienne above, Britain would not be what it is today without Jamaica and Jamaica would not be what it is today without Britain. This relationship produces real and material implications on our experience as Black people living in Britain. Thus to proclaim that Britain has zero influence on your identity is quite fallacious. There are diverse and varied experiences that can attest to the experience of Britishness, unique to Black Brits:

Watching Blue Peter, 4 O'Clock Club and recognising black faces in children's media (acknowledging the significance of representation)

Socialisation into British values and behaviour e.g. engaging in surface level small talk, minimal eye contact (recognising how this contradicts with ethnic values related to expressive engagement and dialogue)

The experience of covert racism and having to be abundantly aware of your race (for many back home in Africa or the Caribbean, racism as a dominant structure does not significantly characterise society because the population is predominantly black)

The experience of being Black-British, also as already asserted by Tik Tok, does and can capture the development of grime and jungle and more lighthearted things such as eating Morley’s on the street with your friends. Ironically, this recognises that culture is expansive and is legitimated by shared experience. To be British is not just fish and chips and to be Jamaican is not just jerk chicken, but it is perhaps how you experience these things and how the underpinning culture informs who you are and what you are becoming. I think it is difficult conceptually for humans to grasp this concept of hybridity because it asserts an obligation to be comfortable with identity not being fixed. Upon accepting this, I think the debate becomes immediately less egotistical and convoluted. You can know a lot about your heritage, and feel deeply connected but still not be able to directly relate to those that live there, in the same way that they will not be able to directly relate to us. The shared racial oneness across the diaspora can still unite us whilst we acknowledge this difference. And maybe cultural identification can be operationalised through the intensity of proximity you feel to the culture, which naturally will vary at times. Ultimately, we don't create culture on our own and we ought to accept that its fluidity will inform our own cultural identities as Black Brits.

Conclusion?

I came to Kiara with an idea of writing about culture but not a set plan. All I knew was that I wanted to discuss legitimacy and feeling, to talk about our experiences as being British-Jamaicans. It has unravelled into a conversation about the existence of A Black-British identity. Our key argument is that culture is fluid. We do not form cultures on our own, and we ought to accept that this nature of culture informs our identity as Black Britons. Moreover, whilst the culture is still evolving, it does not mean that the Black-British culture is not legitimate within its own right. It does exist, and has for a while, but what we must remember is that what it meant to be Black-British 20 years ago is not what it means today.

Ultimately, our message is an invitation to reflect on and interrogate your Black-British identity. What shapes your experience as a Black person living in Britain? The aim of our article is to expand the discussion around culture and identity, recognising that our perspective is just one among many. We understand that our views will continue to evolve alongside the broader discourse.

It’s okay not to have all the answers or to struggle with articulating your feelings about identity. The Black-British identity is complex and diverse, and our sense of belonging will always be personal and political.

*Slavery was not abolished in Jamaica until 1833. The transatlantic slave trade was abolished in 1807.

Resource Pack:

Stuart Hall, Cultural Identity and Diaspora (1990)

Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (1963)

Brian More and Michele Johnson, Neither Led Nor Driven: Contesting British Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica, 1865 - 1920 ()

Catherine Hall, ‘Entangled Histories: Britain and Jamaica in slavery days and beyond’

I was also not allowed to watch Harry Potter😔This is a much needed discussion within the Black-British community, the differing views and experiences within the culture does not eliminate us from having one. The divide probably comes from our grandparents generation with some black people getting better treatment than others leading to disdain from both groups. I found out the other day that my Grandfather - born and raised in Nigeria - went to the university of Reading! My aunt, also born and raised in Nigeria, spent two years at my secondary school decades before me. All this to say being of African descent will always have some relation to ‘Britishness’ whether it’s obvious in the examples stated or whether it’s implicitly through the mark of colonialism.

yes, culture does not eliminate us from having for sure! that is also so cool that your extended family has ties in the Uk! ultimately, I think we are doing the work to interrogate how we feel by having these discussions and understanding the origins of our sentiments. I think compared to our forefathers and mother, we are better equipped and have the toolkit to examine culture and identity, whilst accepting our inter-diasporic differences.